Client-Side Encrypted Posts in Jekyll

I’ve been wanting to write more personal things on this site. Not everything needs to be public, but I still want the convenience of having it all in one place - searchable, linkable, backed up in git.

So I built client-side encryption into this site.

The Use Cases

Personal notes: Things I want to write down and revisit, but don’t need (or want) the world to see. Medical notes, financial planning, relationship reflections. The kind of stuff you’d put in a private journal.

Family/friends reference pages: I can create pages with practical information - emergency contacts, account details, family recipes with stories attached - and share the passphrase only with people who need it. Different pages can use different passphrases, so I can have a “family” key and a “close friends” key.

Draft posts: Sometimes I want to write something and sit with it before deciding whether to publish. Now I can commit it encrypted, let it marinate, and decrypt it later when I’m ready to share (or not).

How It Works

Content is encrypted before it ever leaves my machine. The pre-commit hook catches any file with encrypted: <keyId> in its frontmatter and encrypts the body using AES-GCM (256-bit). The passphrase never touches the server - it’s derived into a key using PBKDF2 with 100,000 iterations.

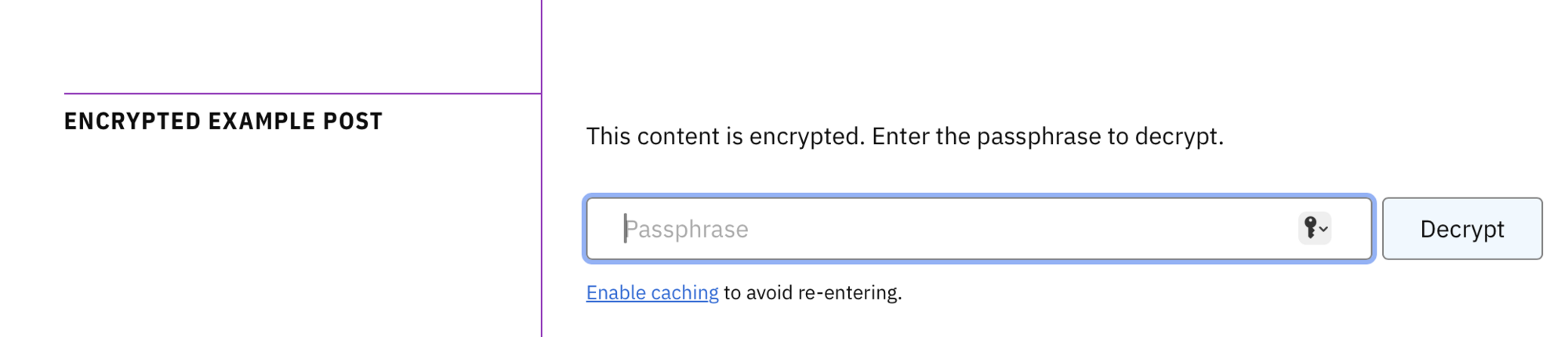

When you visit an encrypted page, you see a simple form asking for the passphrase. Enter it correctly and the Web Crypto API decrypts the content right in your browser. The decrypted markdown gets rendered to HTML using marked.js.

Wrong passphrase? The verification hash catches it before decryption even starts - no garbled output, just a clear error message.

What the Server Sees

Nothing useful. The encrypted payload looks like this:

encrypted_payload:

keyId: default

salt: p6VhCyW0PcurHoiME9ySwg==

iv: DfMMwroAoNKdr5UA

ciphertext: /FcGWHJCVBE8KGYfRoyInrDBEQt2Bk6mqc...

verify: 514fdb92

The salt is random bytes used with PBKDF2 to derive the encryption key from the passphrase. The IV (initialization vector) ensures that encrypting the same content twice produces different ciphertext - without it, identical plaintexts would produce identical ciphertexts, which leaks information.

The verify hash is for better UX: it’s the first 8 hex characters of SHA-256(passphrase + salt). Before attempting decryption, the browser computes this from the entered passphrase and compares it. Mismatch? Wrong passphrase - no need to attempt decryption and wait for a cryptographic failure. AES-GCM would eventually reject it anyway (it’s authenticated encryption), but the verify hash makes failures faster and error messages clearer.

None of these fields help an attacker. Without the passphrase, it’s all noise.

Brute-Force Resistance

The 100,000 PBKDF2 iterations slow down attackers, but don’t stop them if the passphrase is weak. A high-end GPU can still try around 100,000 passphrases per second. That means:

- A dictionary of common passwords: seconds

- A short 6-character password: minutes

- An 8-character alphanumeric password: days (with enough GPUs)

- A 20+ character passphrase: effectively unbreakable

Passphrase length matters far more than iteration count. Each additional character multiplies the search space. Use at least 20 characters - a few random words strung together works well and is easy to remember (also provided by default with the Apple Passwords manager I use).

AES-256 itself is unbreakable (2256 key space). The weak link is always the passphrase.

Passphrase Caching

By default, you have to enter the passphrase every time you visit an encrypted page. This is the secure default - nothing persists.

If you want convenience, you can enable sessionStorage caching in Settings > Privacy. This remembers the passphrase for the duration of your browser tab. Close the tab, it’s gone. It’s a reasonable tradeoff for pages you’re revisiting frequently in one session.

I chose to make caching opt-in rather than opt-out, because XSS scripts you have running in your browser (e.g. from extensions) could exfiltrate the passphrase if they know to look for it in sessionStorage. The kind of content worth encrypting is the kind worth being careful with.

Try It

I made an example encrypted post you can test. The passphrase is your-long-passphrase-here if you want to see it work.

The implementation lives in a few places:

-

utilities/encrypt_pages- Ruby script for encryption/decryption -

assets/js/decrypt.js- Browser decryption module - README - Setup instructions

It’s not complicated. The Web Crypto API does the heavy lifting. I just had to wire it together in a way that fits into a static Jekyll site.

Reference

| ← Previous | Next → |

| Encrypted Example Post | The STREET PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY techniques of Joel Sternfeld via Jamie Windsor |